Richard Johns

In 1963, David Hockney was a rising star of the British art world. A year after graduating from the Royal College of Art, he was working towards his first solo exhibition in London when he was commissioned by the editor of the Sunday Times Magazine to travel to Egypt, with a view to making a series of drawings for inclusion in a future issue.

Hockney spent the best part of a month in Egypt, exploring the Cairo Museum and relishing café life in Alexandria and Luxor. He later looked back on his first visit to the country as a great adventure. ‘It was a marvellous three weeks,’ he recalled. ‘I drew everywhere and everything, the Pyramids, modern Egypt, it was terrific. I was very turned on by the place’.[1]

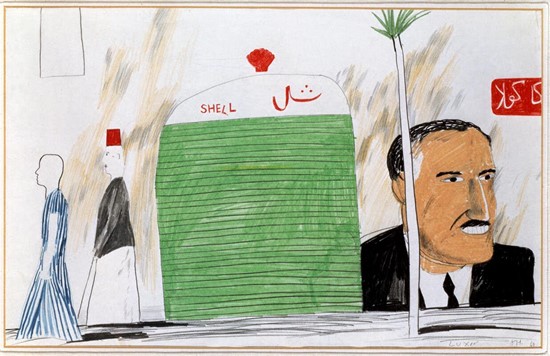

Shell Garage, Luxor, is representative of the 40 or so drawings Hockney made during his visit. It represents a street scene with two figures – a boy and an older man – walking past a petrol station. A larger-than-life portrait of the Egyptian president, Gamal Abdel Nasser, shown as if painted on the garage wall, is brought to life by the artist’s crayon colours. The sign cropped by the right edge of the paper is an Arabic advertisement for Coca Cola.

Hockney’s drawings were never published by the Sunday Times. One suggested reason for this is that the assassination of John F. Kennedy on 22 November – less than 48 hours before the agreed publication – prompted a last-minute redesign (although in the event only the main newspaper was reprinted). Another possible reason for the editor’s decision to shelve Hockney’s drawings was that they confounded expectations of how a British artist ought to represent Egypt.

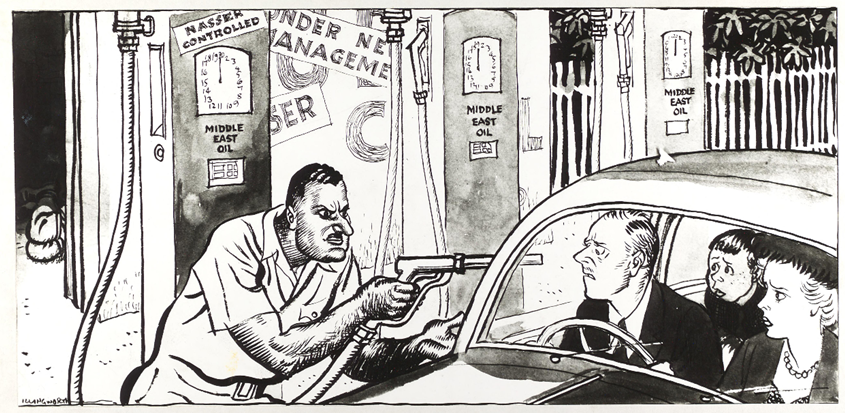

Hockney’s assignment came seven years after the humiliating withdrawal of British forces from Egypt, following the naval bombardment and invasion of Port Said in 1956 – an act of imperial aggression provoked by Nasser’s decision to nationalize the Suez Canal Company. The Egyptian president was routinely portrayed by the establishment media in Britain as a tyrant whose anti-imperialist rhetoric and vision of a pan-Arab union posed a direct threat to British interests. Meanwhile, the Sunday Times and other titles offered readers an alternative, colour-supplement vision of Egypt as a distant and long-dead culture – a land of ancient temples, painted tombs and Tutankhamun.

Today, on the other side of a long and highly productive career, Hockney stands as the most canonical of modern British painters. His early Egyptian drawings earn a place in the British Art UnCanon for their youthful exuberance, for their visible delight in the urban experience of the modern Arab republic, and for their refusal to conform to an old colonial cliché.

January 2022

[1] David Hockney interviewed by Christopher Simon Sykes for Hockney: The Biography, Volume 1: 1937-1975, London, 2011, p. 135.