If the canon is defined as the ideal standard against which all else is measured, Jo Spence (1934-92) disrupted the canon at every possible opportunity. She called herself a ‘cultural sniper,’ firstly because she was ambivalent about the title ‘artist’ choosing to focus on the social function of art, but also to state her position in relation to the art world. She was a sniper, on the outside looking in. She eschewed many of the conventions that might peg someone as a ‘professional’ artist, as is evident in the choice of materials and methods of display in one of her early works, Beyond The Family Album (1979).

Born in Essex to a working-class family, Spence’s parents were factory workers and sent her to secretarial college, which led to her working as a secretary in a photographer’s studio. She then began her working life as a commercial photographer, until she discovered that she found the process of making money by taking idealised images of a largely powerless subject distasteful. Spence formed and relied on networks to find support and develop her artistic voice. With fellow students from the London Polytechnic College she formed The Polysnappers and later the all-female photographic collective, the Hackney Flashers.

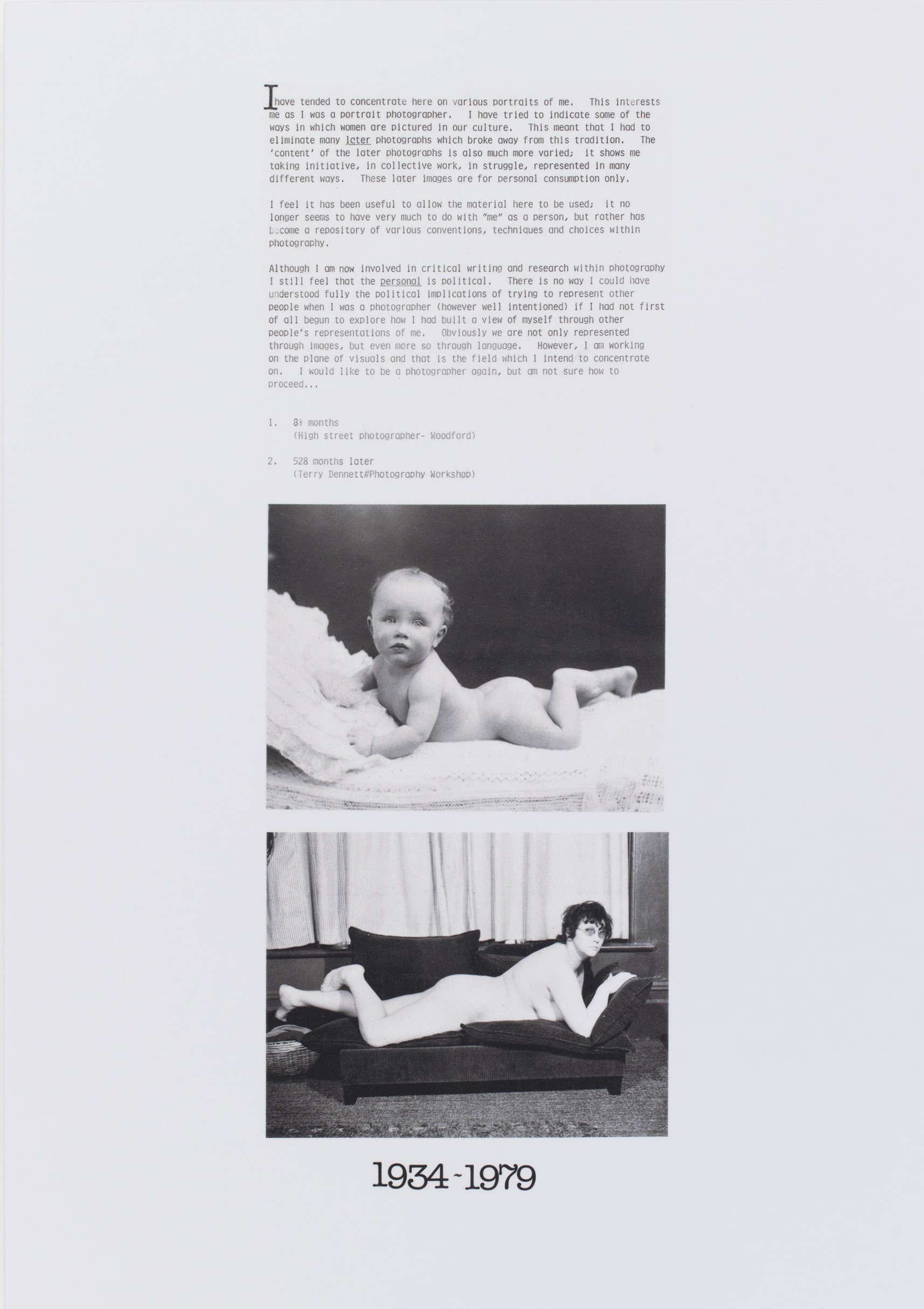

Beyond the Family Album (1979) is a series of laminated panels presented as a collage of short texts, personal photographs and ephemera. Spence turns the familiar construct of the family album on its head, exposing the hidden labour shouldered by working-class women through childcare, homemaking and generally existing in a patriarchal society. Subversive humour brings you into the work as the first panel juxtaposes two images; one of Spence as an angelic looking baby posing on a furry rug and below a recreation by the adult Spence striking a similar post. From panel to panel, Spence deconstructs the stereotypes which pervade our psyche and create the unrealistic and unachievable standards expected of women.

Beyond the Family Album was produced at very little cost. Bucking the convention for editioning work, it was photocopied an unknown number of times, laminated, affixed to community centre walls with gaffer tape or with drawing pins jabbed through the corners, and probably eventually binned. In rejecting the mainstream art world and its restrictive expectations, Spence also rejected its conventional polished display methods. Creating a ‘beautiful’ object wasn’t the point: what was paramount was that the work reached the communities it was intended for.

This work is now in the care of the Arts Council Collection. The Collection itself has to adapt its practices in order to preserve the fundamental function of the piece, and to avoid dampening the work’s potency. In her final letter to her long-time collaborator, Terry Dennett, referred to here as ‘little treasure’, Spence wrote, ‘I don’t want to end up as an “Art Gallery Hack” my work will be sterilized if shown out of context, so “little treasure” keep it polemical and socially useful.’ To faithfully care for this work the Collection must respond to its materiality and the artist’s intention, so standards of care are not clumsily applied as to prohibit the work being seen as the artist originally intended. In bucking against what is expected of an artist, Spence’s practice continues to challenge the conventions of the art collection, asking: ‘are you fit for purpose?’.

January 2022