Graham Gingles (b. 1943, Larne, Northern Ireland) is an artist known for his intimately sized and intricately constructed wall-mounted sculptures.

Having begun his career as a painter, for the past five decades, Gingles has primarily focused his attention on making miniature sculptural environments, which are contained within architectural boxes or vitrines. At times resembling cabinets of curiosity, these highly detailed, hand-made works are perhaps more akin to nineteenth century dioramas or children’s doll houses: mobile theatres onto which we can project our own imaginings, fantasies, stories and neurosis.

Throughout his career, Gingles has tackled, with a stark intimacy, themes of life, death, violence, trauma, sex and belonging, weaving together autobiographical traces and cultural reference points. Having spent most of his life in the North of Ireland, much of his work is infused with references to the politics, culture, customs, history and iconography of the region. His works of the 1960s and 70s are particularly haunted by allusions to The Troubles. Flags, dissected or fragmented body parts, rooms of torture, emblems of conflict adorn the interiors of his boxes from this period.

Often, these sculptures depict, with subtlety, spaces in which the violence of The Troubles occurred and the aftermath of that violence. Gingles has commented that in making these works during the worst of Northern Ireland’s conflict, he found it necessary ‘to find an imagery that was not reportage, that was not graphic, that was not horrible in itself, but which made allusions without describing’.[1] As such, the macabre yet somewhat abstracted scenes contained within his boxes of this time recall the hazy, associative properties and symbolic logic of haunted dreams, or suppressed memories.

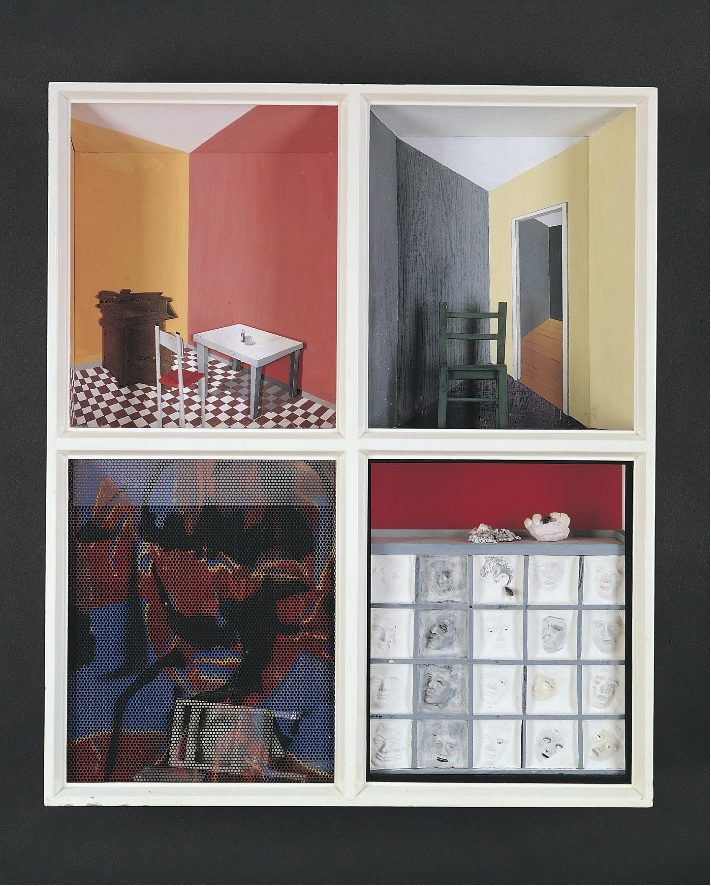

‘White Box’ (1973, Mixed Media), for instance, alludes to the infamous ‘Romper Room’ tortures and killings by loyalist paramilitaries that sent shockwaves through an already traumatised Northern Irish society. In the piece we see a series of four rooms, organised into a grid within a white box-frame. The two top rooms lack any human presence, appearing as stage-sets for as-yet-unperformed actions. Only the presence of an empty chair in each space suggests the anticipation of a human encounter. In the bottom left-hand quarter, we see another space containing a chair, this time upturned, as if it had been hurled to the ground. Here, the scene is enmeshed in a painted gauze, which although abstract, seems to contain the contours of, perhaps, a woman’s face. In the final bottom right-hand quadrant, most of the red-painted space is taken up by what appears to be a cabinet of sorts. Here the curiosities on show are a series of twenty faces, which emerge from the plaster into which they are cast. Grey-white, these isolated portraits form a repository of lifeless masks; indexes of an unknowable horror.

Less interested in mapping the spaces of the Romper Rooms themselves, Gingles’ ‘White Box’ reveals the psychological architecture of the spaces in which the most violent and senseless acts of The Troubles occurred. What we are left with is an impression, an imprint, a trace-mark of the trauma that would continue to seep through Northern Irish society in the decades to come, and which would continue to be a focus of Graham Gingles’ important and singular body of work throughout his career.

January 2022

[1] Art of The Troubles, National Museums NI. Accessed 21 December 2021.