A wooden case from the early twentieth century, once containing a clock designed by Arthur Hey, gives us an interesting object for both studying the history of the railway and the lives of British railway workers across several decades of political and economic ferment.

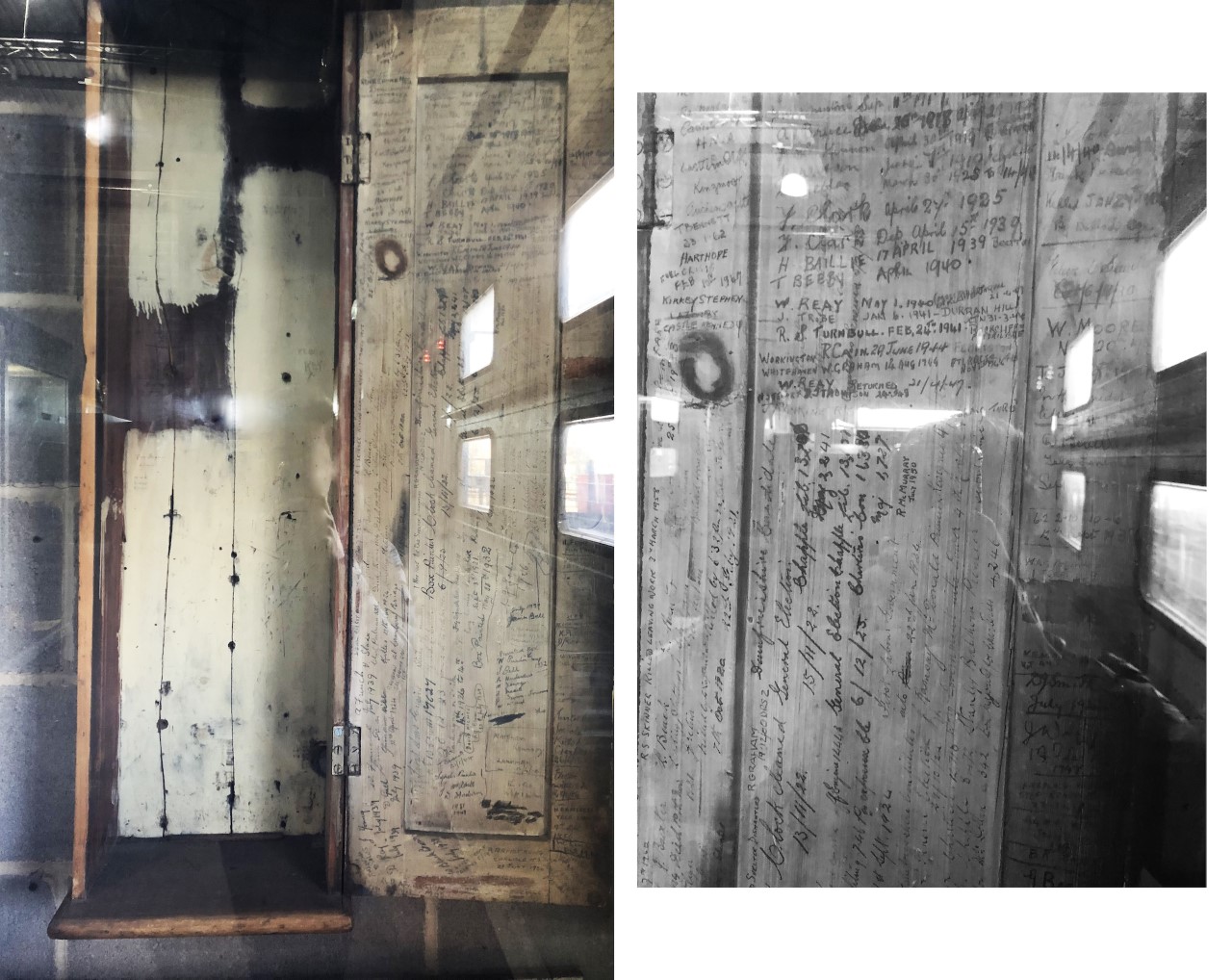

Deep within the National Railway Museum’s warehouse, emptied of its contents, a worn wooden box hangs beneath a plate of glass. Standing at approximately one metre in height, the door of this box has been cast open to reveal a worn interior — two coats of paint therein, distinct in hue, are unmissable. On the interior of the door, one may glimpse a public history of sorts: hundreds of written entries produced by workers who held employment at the Quintinshill post along the now-defunct Caledonian Railway line (1847-1923). This small station, situated along the Scottish border, has been subject to much attention within historical scholarship. It was here that Britain’s worst railway disaster struck: a collision between three trains, resulting from worker negligence, claimed the lives of more than two hundred civilians, many among whom were servicemen and cargo workers returning from duty by rail. It is on the day of this tragic event, that the first entry can be found within the case’s holdings (“22 May 1915”) to mark this occasion and the genesis of this record.

Subsequent entries index a wide range of activities, subjects and national dramas: names of railway workers stationed on the date of entry; dates associated with the painting and restoration of the box; notable deaths in the community; developments occurring on the warfront; incursions led by foreign military agents entering into Britain; marriages in the community; and so forth. These entries are seldom organised chronologically but appear where space permits, produced in varied orientations and with typographic diversity. Some entries are legible to the naked eye, while others are scrawled out to create opaque constellations of text. In a few instances, entries have been covered up and scratched out, thus foreclosing upon any retrograde interpretation.

Taken together, these entries share with us a vernacular record of labour arrangements and historical events across a century of industrial, social and political activity. Such an artefact, produced and updated intermittently by the community, reflects a broader interest in documenting history and life in their shared context. This is form of collaborative work, generated without a sole author or steward, which required each respondent to maintain obedience to a set of rules and record-keeping practices. To this effect, artists and curators often undertake a similar kind of work — recording and exhibiting history in a collaborative, recursive mode under certain conditions or guidelines — to ensure that we do not forsake our past and those who came before us. Indeed, this artefact is a trenchant reminder that while some of the most extraordinary records are drawn up on paper, bound for posterity or make their way into museum collections, public trusts and archives, many compelling records can be found in places we often overlook: in the margins of a recipe, in the background of painting and in this context, in the interior of a clock case. These artefacts give us an image of history; told not from a singular perspective, but one with polyphonous ambitions.

March 2022