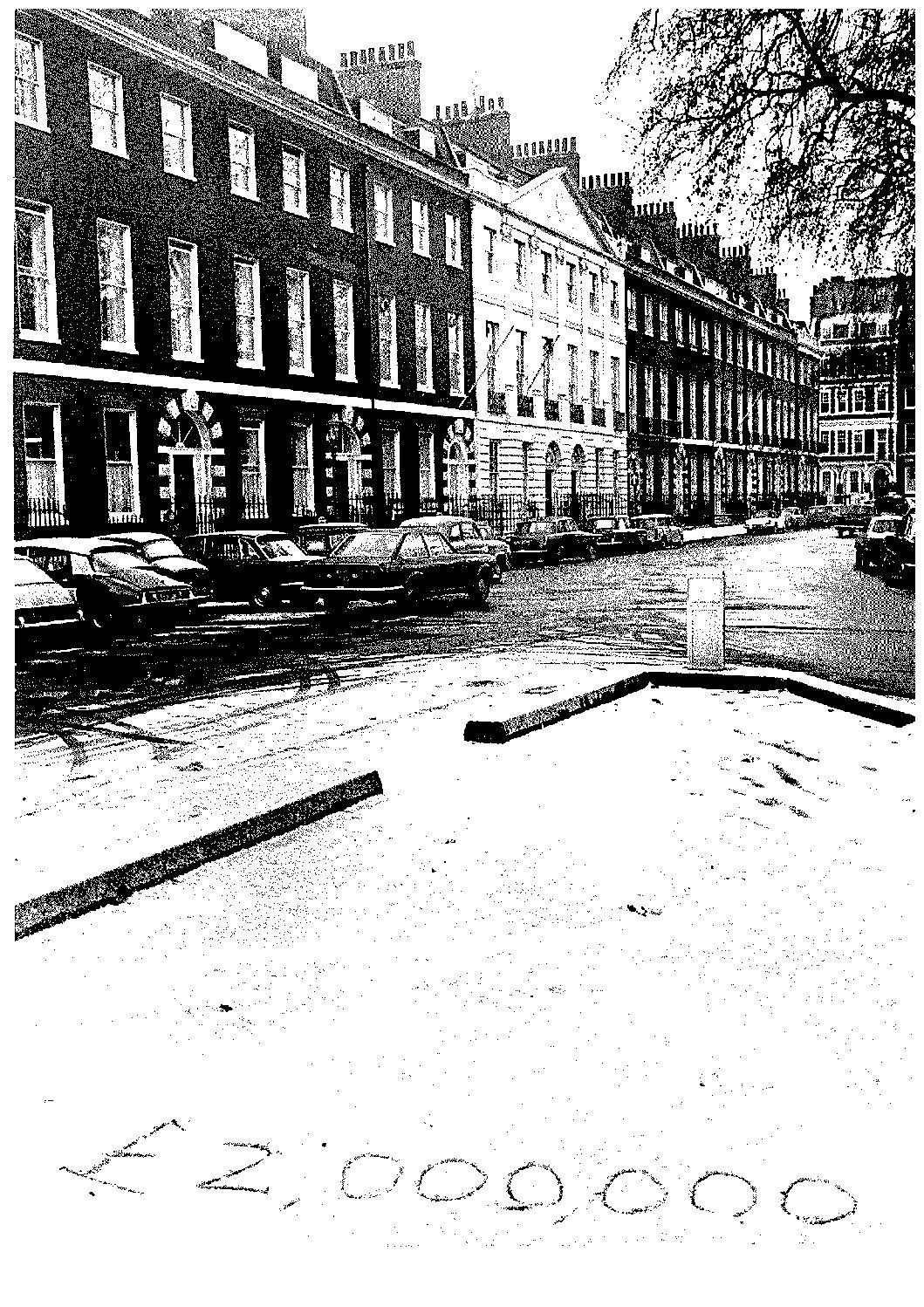

In 1970 the Duke of Bedford offered the fourteen houses on the south side of Bedford Square for sale at £2,000,000, attracting extensive press coverage. The average house price in London at that date was £4,848. Here a local press photographer has inscribed the then-astonishing figure into the snow in Bedford Square itself.

Bedford Square in central London has long been considered one of the greatest artistic achievements of Georgian town planning. Comprising entirely of grand houses built to the highest standard set out by the new London Building Act (1774), it has survived remarkably intact. Although the buildings in the Square were erected by a number of different property developers and their design involved multiple architects, they all had to follow an overall plan. The result was that each side of the Square appears as a ‘palace-fronted terrace’, a symmetrical arrangement of brick houses with a classical frontage faced with bright white plaster at the centre. So, although originally made up of fifty-two private homes, each occupant could feel as if they were living in a palace. Bedford Square has been taken to embody the universal aesthetic appeal of Georgian classicism.

The grandeur and prestige of Bedford Square attracted the elite of society over many generations. In the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries it was occupied by successful doctors, lawyers, businessmen, and wealthy clergymen and their families. In the strictly predictable way that Georgian townhouses were organised internally, the wealthy householders would occupy the main floors, their servants relegated to the attic spaces and the working spaces of the basement areas. Each house followed a very similar floor plan, with rooms always given the same functions, in a pattern that was repeated across London and in many English cities during the Georgian period.

In the twentieth century the private residents left, and offices and educational bodies moved in. Today the Square is occupied by the offices of publishers, fashion houses, and financial service providers, as well as the Architectural Association, Sotheby’s Institute, and the Paul Mellon Centre for Studies in British Art.

Formerly the home of James Wildman, lawyer and agent to William Beckford, plantation owner. Photo: PMC

The cultural capital of Bedford Square has therefore endured over two and a half centuries. But should we accept Georgian classicism as a simple triumph? On closer scrutiny, the Square is by no means as symmetrical or perfect as first appears. Frontages are faked, building standards slip, the details vary more than you might expect. And what of the society that gave rise to such seemingly timeless grandeur? The building of Georgian Bloomsbury coincided with growing investment in slavery and slave plantations among Britain’s wealthy – including a number of Bedford Square’s early residents.

The grandest Georgian townhouses may embody, as one architectural historian puts it, ‘a timeless quality that offends few and attracts many’. But Georgian classicism arose with, and arguably helps mask, a society and economy based on profound inequalities and violent divisions. The enduring aesthetic appeal of Georgian architecture means that these disparities are reproduced and allowed to pass, only perhaps apparent when we confront the shocking reality of raw economic value – as the press photograph relating to the sale of the south side of the Square in 1970 brilliantly exposed.

January 2022