New for 2022

This group aims to address the historic absence of disabled artists and the active exclusion of disability as a compelling subject for visual art. The group will expand the field of knowledge on historical and contemporary British disabled artists and produce new frameworks that increase understanding and expertise around this previously avoided subject.

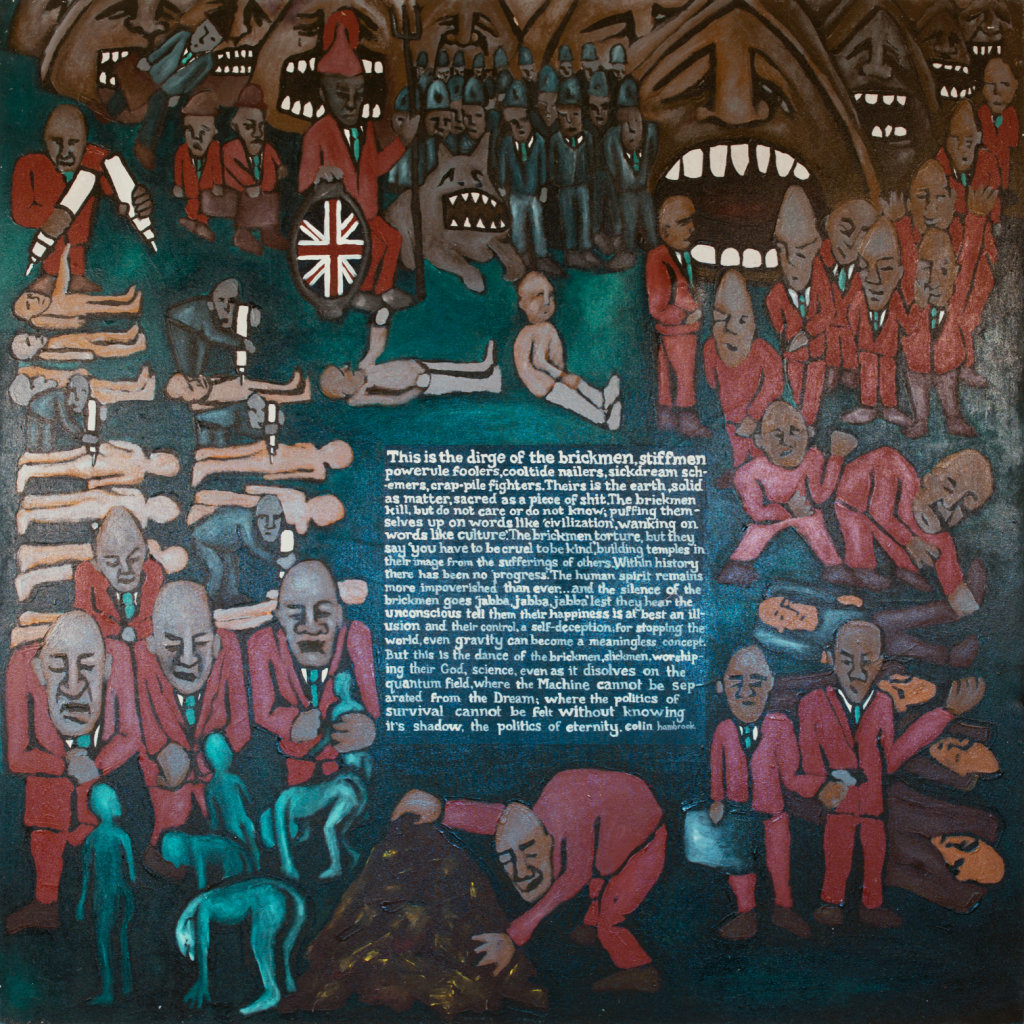

The lack of visibility of disabled people in the arts is widely evidenced, demonstrating the need to change perceptions towards disabled artists. There are few references to disability in major British collections either in terms of themes, subjects or artists. Disability, when it is addressed, is broadly treated in terms of pathology. The Disability Arts movement in Britain has been avoided by curators and writers of art history for 40 years. There is a gaping absence in curatorial language and practice, which affects the visibility of disabled artists and the perception of disability across the sector. Many artists refuse to identify as disabled or even talk about disability in the context of their work for fear of being side-lined by institutions.

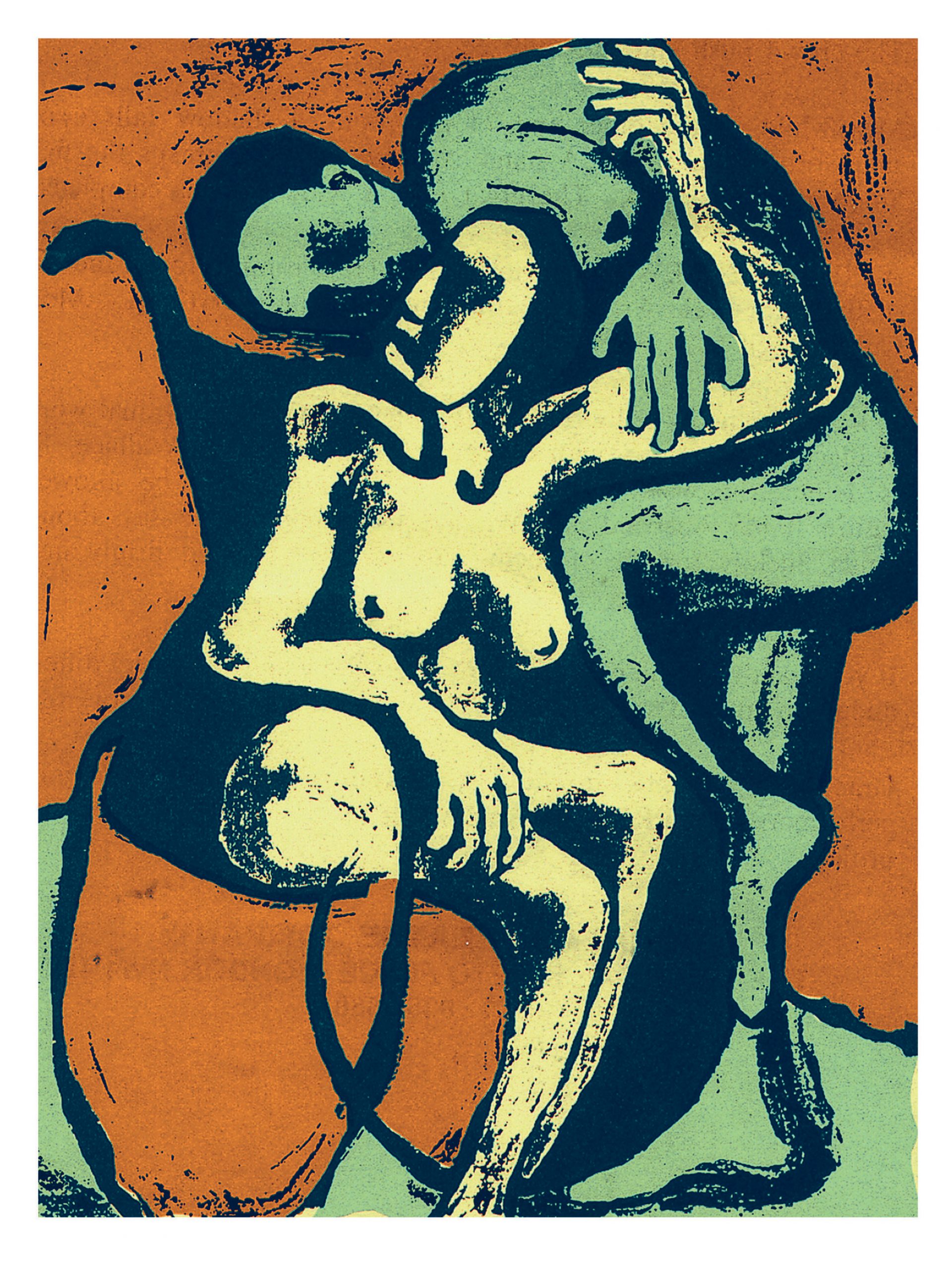

For some artists, disability becomes a catalyst for their creativity, allowing evolution of innovative creative ideas that open up new conversations about humanity and being in the world. We want to explore new ways of articulating disability through curatorial language beyond the usual tropes.

We will investigate historical and contemporary British exhibitions and collections to understand how the subject has been dealt with. We will open up dialogues about artists from the past who are known to have been disabled to explore alternative interpretations of their work. We aim to create new frameworks for understanding grounded in the language associated with the lived experience of disability.

Key research questions include:

- What are the different ways in which disability is treated as a subject in the curation of British Art?

- How might revealing different disability narratives create new opportunities for alternative interpretations of art history and in doing so, how might this lead to increased representation of artists with lived experience of disability?

- How can we create an accessible curatorial language and framework for understanding and interpreting disability representation in visual art, galleries and collections?

We approach disability from the social model perspective. This encompasses all disabling experiences. The group will include perspectives from a wide range of impairments and health conditions. We acknowledge that many of the ideas, assumptions and conventions for understanding disability come from different perspectives, cultures and communities, often medicalised or seen as deficient. These will be explored in the context of British Art as part of this research group. The group will consist of disabled and non-disabled curators, programmers, artist-researchers and academics.

The Disability in British Art research group is led by Ashokkumar Mistry (artist, writer and curator) and Trish Wheatley (Disability Arts Online).